I mentioned that I have written a lot about Bach on this blog and in fact I have already done a fairly substantial post about this very fugue: How to Build a Fugue. That was way back in December 2011! Instead of repeating myself, I am just going to send you back to that post. Today, I will just talk about the famous prelude to that fugue. Here is the beginning in the original manuscript:

|

| Click to enlarge |

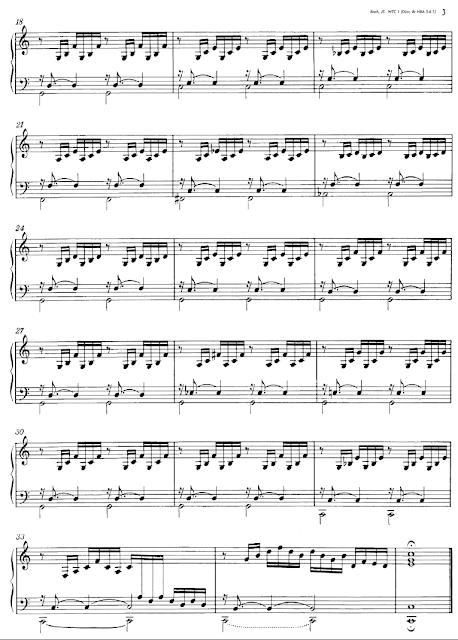

And here is the complete score in the Neue Bach Ausgabe:

The first thing that strikes you about this piece is that, except for the last three measures, every measure has exactly the same arpeggiated layout of the harmony. Indeed, you could do a version that just shows the chords with an instruction "play with this arpeggiation." Here are the first four measures with the arpeggiation removed:

The harmonies are I, ii4/2, V6/5 and I. Perhaps the best way to learn a piece like this is to memorize the chord progression and arpeggio separately and then put them together. This piece is all about harmony as there is almost nothing else there. 19th century editors were so scandalized at one particular passage that they re-wrote it to make it less startling. This is from measures 22 to 23. Here are those two measures with the measures on either side, for context:

I hope that was not too technical! Bach is regarded, by composers, as a great (perhaps the) master of harmony. Soon after his death his son C. P. E. Bach collected together a lot of his chorales in a volume and, in one form or another, that same collection has remained in print to this very day. A copy sits on my shelf. Everything Bach does is within the common practice harmonic system--actually he was one of the main architects of that system. But he was always able to make it sound fresh. Perhaps the most astonishing thing about Bach is that he can write what are very simple, basic progressions, but do so in a way that makes them sound fresh. Just listen how that simple arpeggio enlivens the humdrum and very ordinary progression of the first four measures. And then, throughout the piece, he keeps unfolding more and more extensions and expansions of basic progressions, often using suspensions, as in measure 8, where he suspends the bass B, on its way to the A in measure 9, to create dissonances. But his dissonances always resolve. One thing, as a composer, that I have learned from Bach is that if you prepare a chord with good voice-leading, you can write just about anything.

One more thing to notice is that after we have arrived at the dominant chord in measure 24, prepared by that elaborate progression I mentioned, from there to the end is just one long dominant harmony except for a gesture towards V of IV in measure 32. Being an organist, Bach was, of course, a real master of the use of pedals.

As we go on, with this project, I think we will see how Bach manages to create something new with every prelude. Next time, C minor! Now here is the Prelude and Fugue in C major played by Siebe Henstra on harpsichord:

6 comments:

I think with Bach there is always a linear aspect in his music, which is probably why he was viewed as old fashioned in his time.

Two idle thoughts. First, in the second example if you start in m21 and move to m24 it is easy to see the linear chromatic bass movement from the Subdominant root to the Dominant root. They govern the form of the harmonies rationalizing that movement. Second, the overall arpeggiation used is slightly ambiguous. Is it 2 and 4 or 3 and 3? The ending measures m.32-m34 are particularly interesting in this regard. But m.34 catches itself on the fourth beat by an octave shift all sweet normalcy as if nothing had happened.

If you leave out mm 22 and 23 you get ------- Telemann!

Yeah and if you insert 20 more measures you get Wagner.

and if you repeated the first four measures for seven minutes straight you'd get Glass

Thanks very much for writing this. I am teaching a blind adult student how to play piano. I expect the most challenging aspect to remember a lot of music without having sight to look at sheet music. Teaching chord progressions + arpeggio structure is what I have been planning on doing. This validates my approach. :D

Thanks, Mimi, I appreciate it. I used to do a lot more analytical/educational posts and maybe I should get back to that.

Post a Comment