A recent comment got me thinking because I realized that I didn't agree with the underlying assumption which was that creativity was closely tied to personal expression. This struck me because I am just starting a new composition and it is at times like these that I find myself confronting the basic problem which is, what am I trying to do? It seems odd to say, but I am not trying to express anything personal at all. In my earlier life, I was pretty convinced that this was the job: express yourself. Of course, this immediately leads to the very frustrating question of why would anyone want to hear it? This is the fundamental issue I have with jazz and most pop music which really is about expressing yourself.

I was talking with an old friend yesterday and I described in a few words what is hard about music composition: you have to start by just sitting in front of a blank sheet of paper, staring at it, until something occurs to you. This might take minutes, hours, days, weeks or in extreme cases, years. I've been staring at a particular page in my notebook for nearly a year now and only in the last couple of weeks have started to get somewhere.

I started to think about a new piece for guitar in January, but got nowhere until this month. Slowly some ideas started to emerge and they led to other ideas and so on. Right now I am just considering some basic structural outlines, some pitch materials and relating this to the Greek myth of Hecate. I find that finding a way of relating these three things is a way of generating a musical fabric.

What does this have to do with my personal life and feelings? Nothing, really. This is an act of exploration in an aesthetic universe. It doesn't have anything to do with my personal life as the goal is to go somewhere I have never been.

This immediately brings up the question of why would anyone else want to listen to the resulting music? Well, if it is dull, boring, painful for no reason, or just weird, then, no, I can't think of a single reason. But the goal is actually to come up with something dynamic, stimulating and fresh, so that would be the reason to listen.

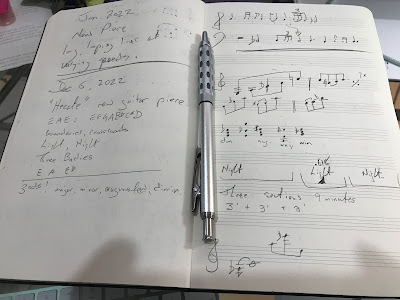

I described how Stravinsky composed the Rite of Spring, in a tiny village in Switzerland over the course of around eight months, spending every day in a tiny 8' X 8' room with nothing more than a chair and an upright piano (and the notebook and pencil, of course!). Speaking of notebooks, the one shown above is my favorite: a Moleskine A5 Music Notebook. I'm not a fan of Moleskine in general as their paper quality seems to have gone downhill, but for my purposes this is perfect. The left hand page is blank and the right hand page has blank music staves so you can jot down both general ideas and diagrams and specific musical ideas. The pencil is also a favorite, a Graphgear 1000 in .5 HB.

Yes, you do have to have some creative spark, which really consists in being able to let your mind freewheel and open to whatever may drift by. But the big challenge is the determination to sit there until something does drift by and the understanding and craft of how to work this idea out and come up with a finished composition. That's really all there is to the "creative process" which is why it is so impossible to teach (though, mind you, nearly every music department has at least one staff member with that job description: professor of music composition. I'm just not sure what they do exactly. Chat about it, I guess. But the important thing is really to provide composers with some sort of regular paycheck!

Let's listen to the fruit of Stravinsky's stay in that little village in Switzerland. This is a recreation of the original costumes and choreography with Valery Gergiev conducting the Orchestra and Ballet of the Mariinsky Theatre:

15 comments:

A lovely post. Yes: imagination is more useful and interesting than expression. That people so often believe the opposite seems a general problem, not just in music. It is depressing how modern 'open-mindedness', born of the dogma that there must be 'freedom of expression', is so infuriatingly unimaginative. But I would say this, being a phlegmatic middle-class Englishman... I recall an essay by the novelist Salley Vickers about how in the modern world we internalise "invisible realities" -- as states of mind and medical conditions -- while older societes externalised these realities as fairies and demons, say. Superstitious creature that I am, I think it is a beautiful observation. And I agree with her that this imaginative, external form of understanding is more useful than an inward, expressive form of understanding.

Thanks, Steven! That essay by Salley Vickers sounds fascinating. Where might I find it?

It's a cracker: https://unherd.com/2022/06/why-we-need-fairies/

Perhaps a supplement and flip side to the observation about cultures that believe in spirits and an unseen realm is to note that in cultures that posit such beings there was an understanding that you could go on a spirit-quest and not find any spirits, or you might find spirits or monsters that kill you. Tribes in the Pacific Northwest had traditions of spirit quests for guardian spirits but it can be easy to forget (or not know if it has nothing to do with your cultural/lineal background) that whether you come across spirits, etc was a proverbial "luck of the draw" as much as it was an indication of spiritual sensitivity.

To say that those spirits are externalizations might presuppose a post-psychiatric explanation of what is being discussed on the one hand and might presuppose what Charles Taylor has described as the "buffered self", a concept of self that is predicated on the surmise that our selves are more autonomous than socially formed but in cultures that posit spirit possession a socially defined self is more normative. One of my friends in my college years from Kenya said there is a proverb in African cultures that says "I am because you are." In cultural contexts where the self is taken to be socially formed the "porous self" is conceived as more open to the influence of spirits in good and bad ways. An African theologian I've read pointed out that in African cultures it's taken that the sexually insatiable and short-tempered are particularly vulnerable to demonic possession or attacks by evil spirits. A re-enchanted world can have a price tag of a less autonomous definition of selfhood that many Westerners might not wish to pay.

Pertinent to my past disagreements with Ted Gioia on what seems to be a white science/black magic dualism I think his duality might make more sense if he bracketed things out into high liturgical sacramentology and low liturgical spirit possession states. The storefront Pentecostal church or the primitive Baptist shape note tradition of Methodist camp meeting group singing are all not exactly rituals but group contexts in which people open themselves up to what anthropologists describe as spirit possession opportunities and Reed Carlson has a monograph on spirit language in the Hebrew Bible that suggests group possession was a thing (which is attested elsewhere in anthropological literature).

But the default that the modern West has been disenchanted prevails in the academy. Ironically, for anyone who grew up, say, Pentecostal, the claim is a bit hard to sustain but feeling the spirit move, as the saying goes, is not something academics cherish these days. It might be that as highbrow art-as-religion evolved in the last two centuries it abjured "fairies" as "superstition" in favor of an art-religion in which people retain "dignity". Meanwhile, for "lowbrow" art-religion the mosh pit or the rock concert has a different idea of transcendence that is rejected by partisans of highbrow who believe that entertaining great art makes you a great person. The late Richard Taruskin staked most of his career on arguing against that dogma and, frankly, I think with cause.

Apropos of nothing 2022 is coming to a close with Kanye West having taking a couple of trippy turns, eh?

I had a somewhat long comment that seems to have vanished into the ether. :S

Charles Taylor has written that the West has a sense of self that is "buffered" whereas many societies have a notion of a self that is "porous". He has proposed, to keep things briefer this time, that there has been a disenchantment in the West influenced by a growing concept of selfhood as autonomous rather than social. But this can be overplayed. Jason Ananda Josephson Storm has been arguing that the Weber style narrative of Western disenchantment is itself a myth about myth and that plenty of people believe in fairies and demons and things like, now probably more than ever by dint of there being more people. Maybe among academics and scholars the idea of a disenchanted West has retained currency for centuries but at a more popular level this isn't the case and hasn't been the case.

A flip side to belief in a world full of fairies and spirits is that people could go on spirit quests to find guardian spirits and come back, so to speak, empty-handed. The tribe my dad was a member of once had traditions about men seeking guardian spirits but just going out in search of them didn't ensure you'd find them or ... to be more blunt, it was acknowledged a person might go hunting for guardian spirits and just end up dead. For cultures that believe in spirit possession it might not be entirely accurate to say spirits are "externalizations" of internal things that are internal from the perspective of contemporary psychiatry or psychology. Anthropologists could cite a variety of ritual and social contexts within which spirit possession can be viewed as a social/cultural script and Brian Levack has some extensive work on this with respect to demonization in western Europe.

Although I still don't buy Ted GIoia's taxonomies I think they would make more sense if he modified them to account for high liturgical (sacramental) vs low liturgical group/spirit possession low liturgical norms. I.e. art religion tends to be thought of in Catholic/Anglican/high Lutheran liturgical defaults in Western thought whereas lowbrow art religion (it surely exists, too) is more the primitive Baptist, storefront Pentecostal church, Methodist camp meeting vibe.

Btw Yoel Greenberg's book How Sonata Forms wipes out utterly the idea that sonata forms were or even could have been invented by any single person. I might have to do a review of the book for 2023 after I've finished it but even halfway through it I can report as much as I just have.

I hadn't heard of Storm, but searching now his book looks interesting, may have to get it... I've heard similar arguments made, yet in my own life I've found little evidence of enduring enchantment among friends and acquaintances. Most people draw on the disenchanted language of 'chemical imbalances' and 'overactive' imaginations, say, to explain phenomenon. Perhaps this is because I'm most frequently in middle-class circles, where a genuine belief in the supernatural is one of the most shocking beliefs one can hold, liable to lead to questions about mental health and sobriety. I also think Vickers' point about how an interest in the supernatural is largely absent from the world of novels is a good one. But yes, this does not necessarily reflect what is believed at a popular level.

I think Storm's case, as I"m reading it so far, is that the myth of disenchantment is a myth within particular enclaves (i.e. middle class and above and college educated and above).

But I grew up Pentecostal in the Pacific Northwest and belief in being slain in the Spirit and spirit possession is normative. I'm not Pentecostal these days (more Reformed/Anglican) but in the U.S. belief in the supernatural is, per Storm's case, far more common than assented to in academic variations on Max Weber's disenchantment thesis.

There's been some variance in scholarship about what spirit possession states are or indicate. The brain imbalance theory might be popular in some circles but Brian Levack has written a book called The Demon Within and pointed out that if the DSM diagnostic criteria and categories keep changing every ten years or so we should be wary of presuming that today's diagnostic alternative to "demonized" is even going to exist in the DSM in another ten years. Ouch. Still, it was a point worth making. Working through Andrew Scull's book Desperate Remedies on some of the ghastly treatments that were fads within mental health care over the last 150 years and ... Scull notes ruefully we're not much closer to understanding "crazy" now than in ages past even if we think we have drugs that will fix things.

Hm, so is the argument that the middle-upper classes have become disenchanted, or that they have wrongly come to believe everyone else has been disenchanted, or both? I guess I'll have to read the book...

I grew up in a very Anglican area, which does not expose you to things like belief in spirit possessions, needless to say! I can understand Storm's theory more with regard to the US -- from where we sit, the culture and politics of the US seems to have a wild and fantastical character that ours does not. I'd be curious to find out if Storm examines different European cultures separately.

IT's looking like he's going to focus on specific thinkers/writers rather than cultures as he's providing an alternative history of Western philosophy to the Weber thesis by highlighting the occult interests of figures from Newton onward and how these have been excised in more textbook histories. Whether he gets to different European cultures separately I'm not sure about yet.

Brian Levack's thesis has been that western Europe was "disenchanted" not by free-thinkers or scientists but by intra-clerical battles between Catholic and Calvinist theologians about the legitimacy of the category of demonization and whether exorcisms were fraudulent or signs of mental disturbance. The Dutch Lutheran Jan Wier (spellings vary too much to use them all) made a case that women accused of witchcraft were not and could not be witches as described in legal charges and should not be put to death; instead they probably needed serious medical attention for depression, which was, it probably doesn't need to be said, was quite a bold claim in the sixteenth century. I've got a book about his life and times written by an Italian scholar who has made a case that free-thinkers and fans of witchcraft conscripted Wier into being pro-witch when he was really just against capital punishment for people accused of witchcraft and was an otherwise orthodox Lutheran doctor who avoided doctrinal fights because he wanted to treat people whether they were Catholics, Lutherans, Calvinists or Jews. I lent that one to a buddy so I don't have the ISBN on me.

But Levack's thesis that disenchantment was a centuries long endpoint of intra-Christian polemic is certainly a different take than the classic Weber thesis Storm has been contesting.

Wenatchee, I found and rescued your long comment from the Spam folder-

That is very curious argument, though I know far too little about the history to make any evaluation of it. It raises the question, to what extend Christian churches have been disenchanted, or have done the disenchanting.

The word 'disenchantment' is annoying me, and I think it's because it's being used to refer to an historical development whereby we supposedly discover that the world never was enchanted in the first place. Whereas for me disenchantment is itself a magical, or countermagical, process, if we want to use that language.

Kanye West, yes wacky and much of the story is beyond my comprehension. Though perhaps your reading on spirit possessions can offer some insights!

Storm promises to explicate that he sees magic and superstition as part of a trio of concepts in which religion is approved piety/practice; magic is borderline/acceptable (there were a variety of Lutherans who were contemporaries of Bach interested in what we would now call occult knowledge, per David Yearsley's intense but rewarding Bach and the Meanings of Counterpoint); and finally superstition as the unapproved/disapproved wing of "secret knowledge". Storm proposes that this triangle delineating a spectrum of official through unofficial to deprecated forms of enchantment is a more accurate taxonomy to describe global human history and that "disenchantment" seems to have been where the formal religious convictions of Europeans past were dismissed as "superstition" by academics within the last two centuries.

In the early Romantic era (Storm cross references, naturally, M H Abrams, there was a belief that disenchantment had occurred but the Romantics believed re-enchantment was possible and THAT, in STorm's appraisal, was what got rejected by later generations of Western intellectuals).

I'll have to read the book, but instinctively I find it a partial view. The industrial revolution also disenchanted more broadly, and in a more visceral and unintellectual way. Carlyle even referred to it as a baleful fiat of enchantment - dark magic essentially. Something which, yes, many nineteenth-century writers, especially of the neo-medieval Christian-/Tory-radical type in Britain, tried to course-correct.

Inherent to aesthetics I think is the experience of the work, which is indeed something different from expression (not just for the contemplator of the work but even for the creator, who is also a contemplator of the work though in extended form due to intimacy with its creation process). The difference is the priority given to the work, as a form that is experienced for its own sake, rather than merely as a medium for conveying the interior state being expressed. But I don't think this distinction cleaves strictly along the "high art"-pop divide, because plenty of popular music (ignoring other arts right now) do make their primary appeal on a sensory level rather than as expression of a particular inner state. Just think of the almost sub-audible vibrations of some hiphop music, or really any riff-based music or dance music, which really is more about the form (and the sensations, including rhythm) than any exact "message" or information that might be considered an expression of an interior state. So when I think of some of Mozart's most beautiful and indeed joyous music, composed at times of great pain and inner darkness for himself, the liberating spirit of art as an experienced object with perfect form rather than expression of internal state...might be just another example of art as distraction and escapism, however refined and perfect the example. Granted, the aesthetic experience need not be one of pleasure or beauty, and its deeper forms take us through emotional territory and not just sensory, but whatever the qualities of experience stimulated by the art object, at some level don't we want there to be a human impulse at its core, and therefore some essence of expression. That's why I am not interested in "art" generated by artificial intelligence, which would be nothing more than computer-generated new variations of previous forms or devices that served as the input from which it is generated by cold dead computation. Expressing nothing and hardly compelling as art because devoid of the humanity that is expressed in genuine creative work.

Wow, this discussion went in some surprising directions.

I have always, uncomfortably, straddled the fence between the spiritual or mystical and the empirical. On the one hand so many of the composers I admire like Bach and Gubaidulina, are strongly religious in their personal lives and their music. But on the other hand, I have little patience with the flakier aspects of the so-called "spiritual" such as new-age mysticism, astrology and so on. Thomas Aquinas was a Christian Aristotelian, which is a pretty good trick. I guess I practice a kind of secular spiritualism because simple materialism really only captures part of the universe.

Post a Comment