|

| Josquin des Prez |

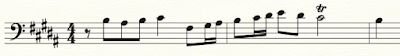

Josquin indeed wedded the logic of math to the magic of melody, and his compositions feel like they unfold with both perfect clarity and atmospheric strangeness. Shining and austere, with the gentle radiance of a shaft of sunlight beaming through a window, Josquin’s music weeded out extraneous, extravagant ornamentation; he created textures of polyphonic complexity that are still smooth and free.His works feel unified because they are organized around small melodic fragments that gradually develop as they are passed from voice to voice. This might seem like a description of, well, all music. But the notion of carrying a melodic “cell” through a whole work was unknown before Josquin’s time, and he was one of the most gifted experimenters with the concept.

Much of the article is in the form of an interview with Peter Phillips, director of the Tallis Scholars and composer Nico Muhly.

* * *

The Whitsun Festival is going ahead in Salzburg and Slipped Disc has the stringent requirements:

TRAVEL REGULATIONS for ENTRIES FROM ABROAD

As of 19 May, the current restrictions on entries from abroad, including quarantine rules, will terminate. Persons who are tested, vaccinated or recovered from Covid-19 will be able to travel to Austria without quarantine (the exception being travellers entering from high-risk countries with a 7-day average infection rate of over 250 per 100,000).

This gives me some hope I might be able to attend the summer festival.

* * *

The archives of music of colonial Latin America are beginning to be explored: El Mundo/Richard Savino: Archivo de Guatemala review – perfect balance of sacred and profane

The huge cathedral that dominates the central square in the Guatemalan capital was built in stages at the end of the 18th century, after the capital was moved from the city that is now known as Antigua, and quickly became the centre of the lively musical culture that is documented in its archives. Those records contain music by both Spanish and Guatemalan composers. El Mundo’s selection includes some of the imported music, including a beautiful little cantata, Sosiega Tu Quebranto, by José de Torres, but they concentrate on locally produced works, especially those by two successive maestri di cappella at the cathedral, Manuel José de Quirós and Rafael Antonio Castellanos, whose sacred compositions combined the techniques of 16th-century polyphony with the rhythms and harmonies of local dance music, especially a dance called the xácara.

Be sure to listen to the brief musical examples.

* * *

What Makes Music Universal. Yes, this is one of those headlines that promises far more than it delivers. But there are some interesting thoughts:

In the past two years, the debate over whether music is universal, or even whether that debate has merit, has raged like a battle of the bands among scientists. The stage has expanded from musicology to evolutionary biology to cultural anthropology. This summer, in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences, more than 100 scholars sound off on evolution and universality of music. I love the din. The academic discord gives way to a symphony of insights into the meaning of music in our lives. It may be a cliché to say music is the sound of our shared humanity. But it feels transcendent to be in tune with a person from another culture. There’s something alchemical about knowing we share the same biology. Originate from the same place. Share the same desires. But there’s more to the story. My recent adventures in the fields of music research have instilled in me, deeper than ever before, the feeling that music is what makes us human. I also have a new appreciation of what universality in music really means.

The most interesting is a performance by the Ukrainian musical group DakhaBrakha:

Gioia: Substack is the most supportive platform for writers I’ve ever seen. And this support is evident in many ways. They let the writer control all the intellectual property rights. They allow writers to keep 90 percent of the subscription revenues. They let writers maintain complete control over their email list. They allow writers to decide what to charge — or what to give away for free. They provide writers with comprehensive metrics, to a degree that no periodical has ever done in my entire writing career.Here’s the sad part of this story. Newspapers could imitate all of this today — in fact, they could have done it years ago — and maybe enjoy some of the extraordinary growth that Substack is now demonstrating. But newspapers won’t do it. They will never do it. And for a simple reason: Their business model won’t allow them to operate with that degree of support, generosity, and transparency. Just imagine a newspaper that gave 90 percent of revenues to the writers. It will never happen.

* * *

When Paid Applauders Ruled the Paris Opera House

Imagine you are in the Paris Opera House, circa 1831. Take a look at the crowd. They look like regular opera-goers, just like you, but some of them are not as they appear. See that row of men clapping wildly in the front row, and crying “Encore, encore?” They’re actually employees of the theater, just like the musicians. That woman dabbing tears from her eyes? By day, she’s a professional mourner; by night she brings her talents to the opera house, in order to increase the impact of the melodramatic scenes.

The directors of the Paris Opera saw no reason to leave the success of their performances up to the whims of an unpredictable audience. To guarantee acclaim, they employed the services of an organized body of professional applauders, commonly known as the “claque.” These claqueurs were tucked away throughout the audience, disguised as members of the public.

You know, I think something very similar is going on with the mass media today.

* * *

Classical Music Podcasts Begin to Flourish, at Last

Classical music has been surprisingly slow to embrace podcasting, a medium ideally suited to illuminate its sounds and stories.

But something changed in the last year, with live performances on hold because of the pandemic and the music industry belatedly exploring new platforms: Classical and opera podcasts have begun to flourish.

Established ones have evolved; “Aria Code,” hosted by the cross-genre luminary Rhiannon Giddens, has found new depths of poetry and resonance, and the conductor Joshua Weilerstein’s “Sticky Notes” is experimenting with approaches to score analysis. Others have joined the field, like the Cleveland Orchestra’s “On a Personal Note,” which debuted last April with Franz Welser-Möst wistfully reflecting on the ensemble’s final gathering before the pandemic closed its hall.

* * *

Igor Stravinsky was a chronic self-reinventor. A stylistic and cultural shapeshifter, he was declared both the “most modern of modern” and a neoclassicist (he hated the word). He shook the earth with savage pagan dances and went in for intense serialism and religious orthodoxy, all while declaring that music wasn’t capable of expressing anything at all. What to believe? Are we allowed to love all these works that so intoxicatingly and possibly insincerely contradict each other? Because I do.

Stravinsky was born in 1882 in a wooden dacha on the Gulf of Finland. His childhood home in St Petersburg was across the street from the Mariinsky Theatre, where his father Fyodor was a singer in the Imperial Opera. Young Igor was fixated on the Russian operas of Mussorgsky, of his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov and his hero Tchaikovsky. His own early works follow in their footsteps; his breakthrough Paris ballets stand on their shoulders. He would eventually flee Europe and settle in Hollywood just as the Second World War broke out, reinventing himself once again in the New World.

* * *

Let's end with some Stravinsky: the Symphonies of Wind Instruments is one of his most enigmatic works: