|

| Click to enlarge |

Sunday, February 28, 2021

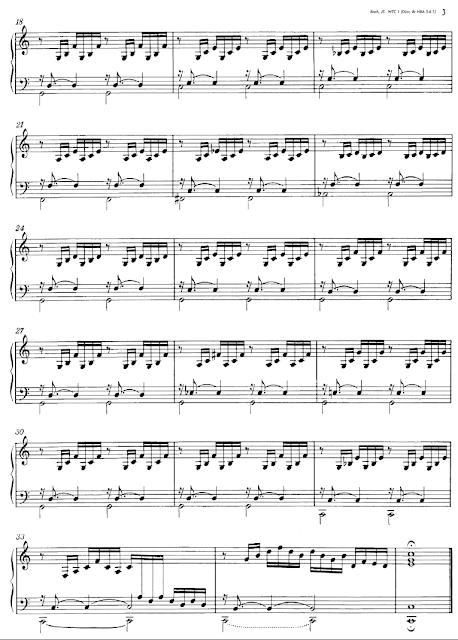

Bach: WTC I, Prelude and Fugue in A flat major

Friday, February 26, 2021

Bach: WTC I, Prelude and Fugue in G minor

The Prelude has such a charming motif that one wonders, if Bach were alive now, would he be writing pop tunes for Katy Perry?

|

| Click to enlarge |

Of course, in the pop song version we wouldn't have quite so distant a harmonic effect as Bach does in m. 17 where he follows a diminished chord on E natural (which should resolve to F) by a deceptive resolution on D minor, which quickly turns to D major, providing a nice V7-i cadence. He then gives us another cadence over a tonic pedal, just to be sure.

|

| Click to enlarge |

|

| Click to enlarge |

Friday Miscellanea

Here's something you don't see every day. Fred Astaire, playing the drums.

* * *

Slipped Disc has a piece with a really interesting bit:

South Korea has the highest classical sales of any country in the world, running at above 20 percent of the total record market.

* * *

Also from Slipped Disc, a cellist plays outside in the snow. They make 'em tough in Tennessee!

* * *

Here is a link to a new documentary on Arvo Pärt.

* * *

Laughter on the Acropolis is a review of a new translation of Aristophanes the Greek comic playwright.

Of his 40 plays, eleven remain. Mr. Poochigian has given us “Clouds” (423 B.C.), a spoof on Socrates, rhetoric, argument and education; “Birds” (414), the Utopian vision of a place that looks a lot like a perfected Athens, but in the air, with birds instead of Olympian gods in charge of the show; “Lysistrata” (411), in which the Real Housewives of Ancient Greece leverage desire in order to end the Peloponnesian War; and “Women of the Assembly” (391), in which women (the idea people and the moneymakers) establish free love, common resources and equality as the basis for a new society.

It sounds almost if they were written last week instead of 2,400 years ago.

* * *

Pretty thin pickings this week, so let's have three envoi. First, the Symphony No. 3 by Schubert, a piece we don't hear very often. Played by Günter Wand and the NDR Sinfonieorchester.

Thursday, February 25, 2021

Discovering Musicians: Alexander Malofeev

I often find myself saying that all the great pianists these days are Russians and I just discovered another one, the nineteen year old Alexander Malofeev. Here he is playing the Saint-Saëns. Piano Concerto No 2 in Madrid this past November:

Also, I'm starting to think that Camille Saint-Saëns is actually rather an interesting composer. A while back I found myself listening to his Symphony No. 3, which has a heck of a finale:

Wednesday, February 24, 2021

Bach: WTC I, Prelude and Fugue in G major

This prelude and fugue remind us that Bach was a very virtuoso keyboard player and he lets it rip in both these pieces. The prelude is in the unusual mixed time signature of 24/16 on top and tempus imperfectus (or 4/4) on the bottom, which just means that there are six sixteenth notes to every quarter note.

|

| Click to enlarge |

And the beginning, in inversion:

Monday, February 22, 2021

What's Up With the Music Salon?

We just had a great discussion in the comments about my post The Objectivity of Musical Quality wherein I argued that there is such a thing as objective musical value which is why we see composers like J. S. Bach and Beethoven as being highly respected and enjoyed over centuries. Mine is a conservative view, but I make no apologies for that. When I started this blog, it was just out of personal enjoyment. But I soon realized that my many years of teaching in conservatories and universities meant that I instinctively took an educational approach. As my work on composition has grown over the years (ten since I started the blog in June 2011) I have focussed more on contemporary music, but, I hope, without losing touch with the main corpus of classical music. While I occasionally wander into world and popular musics I make no claim to much knowledge or experience in those areas.

What I do realize is that perhaps the core purpose of the blog is to appreciate and transmit knowledge of the riches of Western Classical Music--the canon in other words. This has come under increasing criticism in recent years, but to me that is all the more reason to do something like this blog. There are lots of reasons why it might not be easy to become well acquainted with the musical traditions from 11th century Notre Dame up until our time, so I will keep plugging away at it.

Years after I left university I was shocked to realize that in eight years of music history and theory we never took a close look at any Beethoven piano sonatas and only one Haydn String Quartet. We analyzed a lot of Bach chorales, but never the Mass in B minor. The only time I had a course that really dug into a Bach fugue was a doctoral seminar. I'm sure my experience is not unique. It is hard, in a normal bachelor of music degree, to really get to know the Western corpus. You get little fragments only. Part of the reason is time. But another reason is that a lot of professors think of the mainstream canon as being old hat and not worth examining. This is an artifact of their own graduate work when they had to find a new area to examine in their dissertations and had to avoid, for example, standard repertoire.

All this comes down to the problem that a lot of people, audiences and even musicians, don't know the basic repertoire very well. I know I have become far more familiar with it in doing this blog.

This is an "unwoke" blog, meaning that I am not trying, indeed actively avoiding, any political crusades. This was a decision made years ago and it was a happy one. The only time I will mention political issues is if I see them directly impacting on the pursuit and enjoyment of classical music.

Let me hasten to say that I have derived great enjoyment from popular artists such as the Beatles, the English Beat, Talking Heads and Kanye West as well as from world musics all over Asia and Africa. But, as I said, I have no special expertise in those areas to share so I don't talk about them very much.

Bach: WTC I, Prelude and Fugue in F# minor

The prelude is one of Bach's very dynamic pieces in running sixteenths with falling 5ths sequences and two cadences on C#. At less than a minute long it provides a foil for the more extended and very different in character fugue. Regarding the fugue, and especially its subject, Joseph Kerman comments:

It is as though having invented the most emotion-drenched subject/countersubject unit he could, Bach wanted to see if he could sustain a fugue with nothing else.

Here is that very unusual subject with its troubling halt on the third note:

|

| Click to enlarge |

And the countersubject:

| Click to enlarge |

The sobbing countersubject sounds as if it might have come from an aria in the St. Matthew Passion. Given the expressive strength of this material, Bach doesn't alter it apart from two inversions of the subject in the second half. There is also little modulation except to the dominant. One entry of the subject, in measure 25, is hidden with a melodic variation of the first two notes. Again, he uses the occasional rising fifths sequence. Just before the end and fitted to the long note in the last statement of the subject, Bach inserts a particularly biting harmony: an augmented chord on C# (C#, E#, A = G double-sharp). Both the prelude and fugue end with a tierce de Picardie.

Here is a performance by Sviatoslav Richter with the score:

I use the Richter recordings so much because they are the only ones with the score. There are certainly other fine performances!

Sunday, February 21, 2021

Bach: WTC I, Prelude and Fugue in F# major

The Prelude and Fugue in F# major have a jaunty air. The flowing sixteenths of the prelude in 12/16 meter outline triads and offer syncopations to the striding bass line. Bach takes us through a variety of keys: C# minor, D# minor, A# minor and G# minor--before returning to the tonic. A dominant pedal with a hint of the Neapolitan of the dominant, D major, takes us to the final cadence.

The Fugue is a bit more complex. The subject begins with a strong tonic flavor and this "head" motif will assume greater importance later:

We have three quick entries of the subject but after the third a new motif is introduced that acts very much like a new subject, except it is a bit too short. Call it a prominent countersubject, even though it is not actually used to accompany the subject!Saturday, February 20, 2021

The Objectivity of Musical Quality

Possibly the biggest, and certainly the trickiest question in musical (or any) aesthetics is the question of objective aesthetic value. Many people, including recent interlocutor Ethan Hein, deny that such a thing can even exist. I have argued before that it can.

Perhaps we can turn the question upside down: is it possible for Ethan and I to agree that such-and-such a piece of music is utter crap, objectively? Even that modest goal would prove my claim that objective aesthetic quality in music does indeed exist.

For me, when I look around and see the remarkable popularity and longevity of the music of people like J. S. Bach, or Antonio Vivaldi, or, yes, Beethoven, it is, for me, a very small step to say that there must indeed be something objectively there other than mere personal preference. And this is not just about classical music: the longevity and respect for the music of Miles Davis, for example, is another indicator of objective musical quality.

One argument for objective aesthetic quality is that one's tastes change both as one grows older and as one becomes more educated in specific musical styles and genres. You might say they evolve, as one certainly has the impression of understanding and appreciating the music better. On first acquaintance with, say, Haydn string quartets, one may find them an amorphous mass of musical nattering. But on further listening you start to hear differences both of technique and of quality. You are becoming aware of the objective qualities of the music.

Indeed, perhaps the most outlandish claim would be the one that there is absolutely no such thing as objective musical quality. Everything is absolutely relative to every person's individual preference. I'm pretty confident that I can walk up to almost any stranger, at least in the Western world, and ask if they have heard of Bach and they will answer, yes, of course. Why? Because the music of Bach is of such objectively high quality that everyone has heard of him. Otherwise how would you explain it?

Friday, February 19, 2021

Friday Miscellanea

Amid the dire Covid warnings, one crucial fact has been largely ignored: Cases are down 77% over the past six weeks. If a medication slashed cases by 77%, we’d call it a miracle pill. Why is the number of cases plummeting much faster than experts predicted?In large part because natural immunity from prior infection is far more common than can be measured by testing. Testing has been capturing only from 10% to 25% of infections, depending on when during the pandemic someone got the virus. Applying a time-weighted case capture average of 1 in 6.5 to the cumulative 28 million confirmed cases would mean about 55% of Americans have natural immunity.* * *One of the best streaming series during the pandemic has been the one at Wigmore Hall. And they are steaming ahead: WIGMORE HALL LINES UP 200 UK MUSICIANS FOR 40 CONCERTS.* * *

And here is more good news: Missing your culture fix? Good news, Glyndebourne will return this summer.

Glyndebourne has just confirmed that it will proceed with its annual opera festival this summer. Like most events in our pandemic age, many alterations will be made to ensure that social distancing and other safety precautions are in place - audiences will be capped at 600, which is 50 per cent of the 1,200 person capacity, and entrances to the festival's famed fine dining experiences will be staggered - but the prestigious event's announcement is the first sign that the traditional British summer season, however altered, may be back on track.

* * *

How Bang on a Can helped remake the world of new music:

These days, Bang is a sprawling artistic conglomerate, with an annual budget of $2 million to $2.5 million, a dedicated record label, a virtuoso chamber ensemble (the Bang on a Can All-Stars) to carry its branding internationally, an active commissioning program, a summer residency and a distinctive performance format — the new-music marathon concert — that is practically a trademarked part of the organization’s identity.

The Bang on a Can Marathon, in fact, is one of the few musical ventures to make a graceful transition to the COVID-era virtual concert hall. The latest installment is scheduled for Sunday, Feb. 21, with four hours’ worth of premieres by Eve Beglarian, Gabriel Kahane, Jakhongir Shukur, Alvin Lucier and others.

* * *

Here is a really interesting look at business models and music: Five Ways Classical Music Is Pivoting.

According to Eric Ries, author of The Lean Startup, there are ten different kinds of pivots. At least six out of them are relevant to classical music.

• Zoom-in Pivot: A single theme or event of the original season becomes the focus of the entire season.

• Audience Segment Pivot: An event is a better fit for an audience outside the core audience, requiring a new audience segment.

• Business Architecture Pivot: A venue or arts group switches from a low-volume/high-margin to a high-volume/low-margin model.

• Value Capture Pivot: A venue or arts organization changes how it collects revenue from customers.

• Channel Pivot: A venue or arts organization identifies a better way to reach its audience.

• Tech Pivot: A venue or arts organization uses different technology to reach its audience.

* * *

For our envoi, here is a performance of the Rite of Spring in the piano four-hands arrangement with Daniel Barenboim and Martha Argerich:

Thursday, February 18, 2021

Bach: WTC I, Prelude and Fugue in F minor

Some commentators have called this prelude and fugue melancholy, but I hear a profound serenity. Bach achieves this serenity by eschewing the use of all those techniques that push the musical movement forward, such as sequences and stretto. Instead of those methods, which work by stepping up the musical tension, Bach works through a number of different keys and harmonies, none very remote, with frequent cadences. A cadence brings the music to a close and composers, like Wagner, who want a constantly increasing tension, avoid them. Here, there are cadences every few measures. If I could suggest a visual metaphor, listening to this music is like watching clouds slowly move and transform in the sky.

The fugue as well departs from Bach's usual practice: instead of the subject moving from tonic to dominant harmony, this one moves from dominant to tonic harmony. The subject is quite chromatic and the answer is tonal. The countersubject is a very simple anapest figure that is used for all the episodes. That's it really. Subject, answer, simple episode. He makes smooth modulations to closely related keys like C and G major and A flat and E flat. But no strettos, no clever invertible counterpoint, no transformations of the subject. Just subject, answer and episode. Despite the chromatic angularity of the subject the mood is serene calm throughout. That in itself is pretty remarkable.

Here is Sviatoslav Richter and the subject is shown in red in the fugue.

Wednesday, February 17, 2021

Out, Out Damned Spot!

According to the teachers who founded the group #DisruptTexts ... They believe that the Bard of Avon should either be removed from school curricula entirely or rebranded in a way that dumps significant criticism on his work as a symbol of white supremacy and colonialism.

Well, sure, if your entire world view is shaped by ideological concepts, allowing no room for consideration of aesthetic quality, then why the heck not toss old Shakespeare in the trash? But if you are that blind to actual literary quality, how the hell did you become an English teacher? Science too hard? The humanities just offer more opportunities for political power trips and general idiocy?

But if it can happen with English teachers then why isn't it happening with Music teachers? Or does the usual requirement that you actually have some skills in music tend to weed out the whackos?

Monday, February 15, 2021

Bach Not Worth the Trouble of Being Cancelled?

I've puzzled lately over some of the mysteries of progressivism. For example, efforts have been made to "cancel" important artistic figures like Homer, Heinrich Schenker and Beethoven. In some instances this was to clear the curriculum for works by women and people of color, in the case of Schenker it was because he was supposedly a racist and in the case of Beethoven it might be just because he is a really famous composer.

I wonder about Bach: is he going to survive while Homer is cancelled simply because classical music has already been consigned to oblivion by pop music?

I discovered classical music, and Bach in particular, when I was in my late teens, around 1970. In essentially moving my interest and loyalty from pop to classical I was moving contrary to the historical trend. Starting in the late 1950s pop music recordings started to out-sell classical ones. While Van Cliburn could compete with Elvis Presley at the record store, by the time we get to the Beatles in the mid-60s there is no contest. Classical music was well on its way to bing a minor niche in the world of music.

This was not the case in the somewhat different realm of music education where classical music still had huge prestige. It commands more and more in-depth scholarship than does popular music. The latter has taken a long time to infiltrate the halls of academe and the process is still ongoing.

But now there is a new trend, the re-ordering of society according to the demands of social justice. Homer is being cancelled and even Shakespeare is attracting some dubious glances. While an attempt was made to cancel Beethoven, largely unsuccessful, a more concerted effort did result in the dismissal of a music theorist for defending Schenker. Will they come for Bach next? Or is he simply too unimportant to bother with?

If the social justice project, like many other leftist projects, is simply about the claiming of power, then perhaps people like Bach are too minor to be worth the trouble. Beethoven has a more salient political profile, which is probably why he has been attacked.

Bach is, after all, a figure in history with only aesthetic power. His only influence outside pure music would perhaps be in theology--and theology is even more minor in the contemporary world than classical music.

Bach: WTC I, Prelude and Fugue in F major

This spritely prelude and fugue is even shorter than the E major prelude and fugue. In Sviatoslav Richter's performance both pieces together only come to two minutes duration. There are some other resemblances as well: the prelude is again in 12/8 and the fugue has a subject with a lot of running sixteenth notes. But apart from that, this pair of pieces are unique individuals as are all the ones in the Well-Tempered Clavier.

The prelude is dominated by sequences of various kinds with a great deal of exchanges between the two voices. The virtuoso brilliance is enhanced by the extended trills.

The fugue subject begins with a very distinctive motif that turns into running sixteenths which then act as a rather neutral countersubject. There is not much else here other than that subject which appears in succession in the three voices twice, making up the first half of this brief fugue. The second half is dominated by the subject in stretto, again, stated twice at the interval of two measures. The first time the subject appears from the soprano through the alto and finally bass and the second time that is reversed, bass, alto, then soprano. In the middle, there is another stretto, just with the bass and alto. We haven't had this much stretto in a fugue since the very first one, in C major.

Just a little note for those joining us late: a "stretto" is a contrapuntal technique where a subject is layered upon itself giving the music a feeling of hurrying up. It is as if one person interrupts another in conversation by starting to speak before the first person is finished. In a fugue it is not considered rude, but rather an opportunity to both show off the composer's skill and to increase the musical tension.

This fugue is all about entries of the subject of which there are thirteen before a brief episode that closes the piece. And all this in the span of one minute.

Here is Sviatoslav Richter with the score:

Saturday, February 13, 2021

Bach: WTC I, Prelude and Fugue in E minor

Friday, February 12, 2021

Europe called...

Perhaps the most interesting passage in that Guardian article about Caroline Shaw was this one:

Being open to so many influences hasn’t always been straightforward. One of the vocal techniques referenced in Partita was Inuit throat-singing, which Roomful of Teeth studied with two representatives of the tradition. In autumn 2019, another Inuit singer, Tanya Tagaq, claimed on Twitter that Partita was a work of appropriation. Shaw was devastated.

“I stopped any performances of Partita at that moment. We had to figure this out. I fully respect what was said. Then a few months later Covid hit, so we haven’t performed it at all since then.” How does she see Partita working in the future? “I’m going to change the section that I never would have written had the conversation been different 10 years ago.”

There are a number of interesting elements here. Let's take the last one first. She says “I’m going to change the section that I never would have written had the conversation been different 10 years ago.” This raises the interesting question of whether any piece of music--or artwork generally--can endure over time? As they are always finding new things that are no longer permitted, then that raises the possibility that any artwork can become, even over ten years, objectionable in whole or in part. Ten years ago it was "cool" to study Inuit throat-singing and, as a kind of tribute, incorporate it into your work. Now it is "cultural appropriation" and therefore forbidden. That is like a sword of Damocles hanging over any creative artists work. Who knows what new thing will be forbidden ten years from now?

But let's look at this idea of cultural appropriation more broadly. It seems the strangest pole to hang your flag from because all music, and art, undergoes transmutation and "appropriation" in the course of history. One artist even said once that composers don't borrow, they steal. Yes, and if they do it well, it may result in better music than the model. Just look at what Bach did with Vivaldi concertos. If Inuit throat-singers really want to take back throat-singing so that it is a technique only they can use, ok.

But Europe called and wants its harmonic system back along with equal temperament, the violin, cello, piano, guitar and most other instruments. You can keep cymbals as they come from Turkey and the marimba and xylophone as they come from Java. Everything else, including the five-line staff, is cultural appropriation!

Yep.

Bach: WTC I, Prelude and Fugue in E major

We have had some fairly long preludes and fugues, up to eleven minutes in total duration. But this pair are the shortest so far with various performances ranging between two and three minutes in length. Bach has stuck to a fairly small range of time signatures so far, usually what we call common time (C) and Bach would likely have called "tempus imperfectus." That "C" time signature and the one with the vertical slash, both come from the older mensural system that used circles, half circles and dots to show meter and division. But this prelude is in the slightly unusual meter of 12/8, compound quadruple time. The score is a single page, as is the fugue, and Bach reminds us that he, as well as Mozart, can toss off charming melodies effortlessly. The prelude modulates to the predictable B major, then the less-predictable B minor, then F# minor, A major before returning to E major. Towards the end there is a kaleidoscope of keys briefly touched on including G major, B major, C# minor before closing with a chromatically decorated plagal cadence.

The fugue has another of Bach's rhythmically dynamic subjects and one that undergoes no exotic transformations. It is as if he is giving us a rest after the E flat minor fugue. The countersubject is just the turn figure from the subject. Not too much to say about this unprepossessing fugue that delights more than it confounds.

Here is Richter with the score:

Friday Miscellanea

Philosophy, Plato wrote, begins in wonder. At the beginning of thinking there is an affect of astonishment. Will students who grew up with hip hop music experience wonder and astonishment if they’re just taught about hip-hop, its history and its internal grammar? Some may perhaps be surprised that hip hop has a history, as well as historical antecedents, and that there is also a technique of composition, at times complex. But compare that with the radical defamiliarization entailed by exposing the same students, say from urban areas, who listen to pop or hip hop, to the French baroque or to the Art of Fugue. Are we so sure that students who chose to attend music school want to hear and analyze what they are already familiar with? Are we so confident that students in literature want to read and reflect on rap lyrics or Beyoncé rather than Faulkner or Melville or Samuel Beckett? Should colleges and universities situated in rural America teach country music and reality TV? Should they not instead fulfill their mission of exposing students to Fellini and Bergman and urban culture, their mission of taking their students to a different intellectual and aesthetic space?

* * *

The Guardian has this interesting piece. Caroline Shaw: what next for the Pulitzer-winner who toured with Kanye? Opera – and Abba.

When Caroline Shaw became, at the age of 30, the youngest ever winner of the Pulitzer prize for music, she described herself as “a musician who wrote music” rather than as “a composer”. Partita, her winning score, is a joyful rollercoaster of a work, encompassing song, speech and virtually every vocal technique you can imagine. It was written for Shaw’s own group, Roomful of Teeth.

Eight years on, she’s still wary of defining herself too narrowly. “Composer, for some people, can mean something very particular,” she says, “and I’m trying to make sure I don’t get swallowed up into only one community.” Not that Shaw’s range shows any sign of narrowing: even a small sample of her work over the past few years throws up an array of names not often seen together: rappers Kanye West and Nas, soprano Renée Fleming, mezzo-soprano Anne Sofie von Otter, Arcade Fire’s Richard Reed Parry, pianist Jonathan Biss. She has written film scores, sung on others, was the soloist in her own violin concerto, and even managed a cameo appearance as herself in Amazon Studio’s comedy drama Mozart in the Jungle. A year ago, Orange, a recording of her string quartets, won the Attacca Quartet a Grammy.

* * *

From Slipped Disc comes this clip of gangnam-style conductor Yuri Simonov:

Also from Slipped Disc (where else?) is this collection of iPhone sound effects. Sung. A capella.

The modern approach plays out in its new look, which patrons will see on everything from posters outside the box office to tickets to the website and social media. The static typeface of yesteryear, which looks the same no matter where it’s applied, is gone. In its place is a new custom, variable typeface called “ABC Symphony” that evokes the sensation of singing. The typeface “has all the qualities of traditional classical music: sophistication, elegance, slight grandeur,” says Mikolay, but with a key difference: The team gave it a contemporary behavior, so “it can react, stretch, and skew and bend in reaction to sound.” Letters in the same word might be incrementally shortened or attenuated, so the logo, which reads “SF SYMPHONY,” arcs from left to right like a crescendo. Some words lean forcefully to the right for emphasis, like a pianist playing forte.

* * *

Here is a very practical article from NewMusicBox: COMPOSER COMMISSION PAY IN THE UNITED STATES.

The major conclusions we were able to draw from our study are as follows:

The median commission fee for all compositions was $1500, or $150 per minute.

While commission fees were generally under $10,000, there was a sizable portion of outliers – around 11 percent of works – whose fees were between $10,000 and $50,000, or sometimes even greater.

Commissions for small groups or soloists were more likely to be unpaid, or for small fees. Commissions for large ensembles were more likely to be paid, and to command larger fees. Most outlier fees were for large ensemble commissions. The best paying large ensemble was the large choir.

Composers with more experience tended to receive higher fees.

Without taking into consideration factors such as experience level, female composers had a higher per-minute pay rate than males, and white composers had a higher per minute pay than non-white composers (as a group).

The article is a long one with a lot of hard data, so worth having a look at the whole thing.

* * *

For our envoi today, let's have some thing different, a string quartet by Caroline Shaw. This is Entr'acte with the Calidore String Quartet.

Thursday, February 11, 2021

Bach: WTC I, Prelude in E flat minor, Fugue in D# minor

When you are this far out on the circle of fifths it is moot whether you use six flats or six sharps so Bach gives us one of each. D# minor is the enharmonic equivalent of E flat minor, that is, they are the same, but spelled differently. Like fish or phish.

The prelude is a lovely piece that is both a sarabande and an aria, first for soprano and later for bass. There is not too much more to say about it unless we analyze the harmonies in detail. I'm not going to do that, except to say that Bach, as always, shows his great command of harmony, here to create some piercing dissonances that resolve beautifully.

The fugue is a whole other kettle of fish, however! Here Bach really shows all the possibilities of the subject:

The fugue is in three voices and we hear this subject first in the alto, then the soprano, and finally the bass. Then there is an episode with some lovely chromatic passages. Next we hear the subject in stretto with the soprano following the alto one half-note later. After another short episode we hear the subject inverted:

Tuesday, February 9, 2021

Bach: WTC I, Prelude and Fugue in E flat major

In the Prelude and Fugue in E flat, Bach explores other fresh ideas. For example, the prelude is actually more rigorously contrapuntal than the fugue! We tend to think of Baroque preludes as usually being brief, fantasia-like and improvisatory. And often they are. But Bach sometimes makes rather more of them. In this prelude, for example, Bach bases the opening section on the simplest of motifs:

Not only "bases," that is virtually the only thematic material! Then there is a two-measure virtuoso flourish leading to a new section in quarters and half-notes that unfolds a simple theme, but in close imitation at the half-note: |

| Click to enlarge |

In this example you can see the second measure of the flourish and the beginning of the contrapuntal section. It begins with a canon in four voices: first the tenor, then the bass a half note later, then the alto and finally the soprano. This turns into free counterpoint, but bit by bit, the sixteenth notes return until, by measure 26, the first, simple, motif returns and is combined with the canonic idea. This is elaborated and developed over three pages with the first motif and the canonic theme weaving in and out.

Monday, February 8, 2021

A Forqueray Interlude

Here is a lovely piece by Antoine Forqueray, played by Jean Rondeau and Thomas Dunford:

Sounds simple enough, except for all the ornaments, right? Now have a look at the score:

|

| Click to enlarge |

That white notation stuff was supposed to go away when we moved from mensural to modern notation early in the 17th century. But maybe France didn't get the memo? Anyway, I want to transcribe this for guitar, so I am going to try and sort it out.

Bach: WTC I, Prelude and Fugue in D minor

I don't often find myself chuckling when I listen to a Bach fugue, but I did with this one. More about that later.

The Prelude in D minor is the first instance of the use of triplets so far in the WTC. I don't know if a lot of study has been done of Bach's rhythmic techniques, but one thing we notice in the preludes is that each one focuses on a particular rhythmic structure, just varying it enough to be interesting. The typical mistake that beginning composition students make is to have too much variety. After two bars of something they want to do something contrasting. But notice Bach's practice. This entire prelude, except for the final cadence, is in triplets with the bass line in eighths. That's it! The variety comes almost exclusively from the harmonic progressions and the filigree of triplets just highlights that. The modulations are to closely related keys, such as G minor in mm. 6 - 8 and again in mm. 17 - 18.

But the fugue is where Bach really has fun. This piece is all about inversion--not invertible counterpoint, though that can always be present--no, here Bach inverts the subject. Here is the subject in its original form:

Sunday, February 7, 2021

Bach: WTC I, Prelude and Fugue in D major

In this prelude and fugue, at three minutes long shorter than your typical pop song, Bach shows us yet more ways to write a prelude and fugue. The prelude is another moto perpetuo like the C minor prelude, but this one is done differently, with scale passages over a secco bass line. There is a brief fantasia-like passage at the end leading to the cadence. The two big chords are interesting: the first one is viiº7 of I and the second is viiº4/3 of V. Then V-I. I remembered one theory professor saying quite casually that EVERY piece in the common practice period ends with either a V-I cadence or a IV-I cadence. But if I recall correctly there may be a Bach chorale or two that ends with an odd cadence.

The fugue subject is nothing more than a variant of a standard Baroque ornament followed by a brief scale passage. What makes it exciting is the rhythmic verve. We haven't talked about this, but Bach's subjects all tend to be rhythmically really appealing. Here is that subject:

Bach's group of eight notes is a bit different from either, of course, but I see a family resemblance. It you were sitting at the keyboard, just fooling with these ornaments, you might stumble across what Bach uses here. Rhythmically it resembles the double cadence and the trill from below, but he has organized the notes to, instead of functioning in a cadential context, to simply suggest a tonic triad on D. He follows this with nothing more than a scale segment in dotted notes. And that's it. A fugue subject that, while it sounds complicated because of the 32nd notes, is actually very bare bones.

The fugue is quite brief, only 28 measures, but there is room for lots of sequences. Here is an ascending fourth sequence:

Saturday, February 6, 2021

Bach: WTC I, Prelude and Fugue in C# minor

So far Bach has just been getting warmed up by tossing off a few simple and quite short preludes and fugues. Now, with the C# minor prelude and fugue he starts to show off what he can really do. Both of these pieces have rather an antique feel to them which reminds us that Bach comes from a family with deep roots in the world of music. Members of his family were church organists in Germany since the 16th century. The prelude almost has the feel of Renaissance counterpoint with the simple theme echoing itself at the octave then wandering off into free melodic counterpoint.

Let's just review what we have seen Bach do with the fugue so far:

- the fugue in C major was an exercise in stretto where Bach jams in twenty-four statements of the subject in a fugue only twenty-seven measures long. There are no episodes and only two measures of transitional material.

- the fugue in C minor has no strettos whatsoever, but lots of episodes as well as false entries, hidden entries and invertible counterpoint.

- the fugue in C# major is all about developing the motivic material of the subject and nothing else and has a minimum of statements of the subject.

The subject has a venerable ancestry as it can be found in counterpoint going back centuries. Imagine if you were asked to write a long, long fugue with only four notes. And not only make it interesting, make it truly great. That is what Bach has done. I don't have to go over the details as some wonderful person has put up a clip of the piece with all the entries of both subjects shown in red, blue and pink (for when the subjects overlap a lot). Here is the clip:

Friday, February 5, 2021

Bach: WTC I, Prelude and Fugue in C# major

Thursday, February 4, 2021

Bach: WTC I, Prelude and Fugue in C minor

This prelude and fugue are as different from the first ones in C major as could be imagined. Starting with the prelude, it begins with a relentless moto perpetuo using an arpeggiated figure, another one of Bach's happy inventions. Did any other composer ever find so many different ways to arpeggiate chords? Here, the arpeggio always includes neighbor tones and wanders around among closely related keys like E flat, B flat and G major. Towards the end there is a surprising change of texture with a coda in three tempi: presto, adagio and allegro which does little more harmonically than sit on the tonic, tonicize the subdominant and cadence on C minor with a tierce de Picardie (major third). Great piece with a unique rhythmic layout. Towards the end it resembles a fantasia.

This fugue is one that has been extremely popular with music educators because it demonstrates so many features of the genre: false entries, hidden entries, sequential episodes and so on. Whereas the first fugue in C major is stretto, stretto and nothing but stretto, this one hasn't a single instance of the stretto. Instead it has developmental episodes and contrapuntal inversions. But what strikes the listener first is the jaunty, dance-like subject.

A false entry is one where we hear just the beginning of the subject, in this case that very distinctive C, B natural, C motif, but it is not followed by the rest and the actual subject, complete, soon after appears in a different voice. An example is found in the second half of m. 10 where that beginning motif, in this case, B flat, A natural, B flat, is found in the alto voice, followed by a couple more notes from the subject, but it does not continue but is instead interrupted by the real subject in the soprano in the next measure on E flat.

The design of the fugue is fairly simple, one reason is it popular with those teaching how to write fugues. There is the subject with its characteristic lower-neighbor ornament and two downward leaps, first a fifth and later a sixth. The subject is accompanied by two countersubjects, the first in mm 3-4 joined by the second in mm 7-8. Bach manages to use nearly all of the possible inversions of these three elements: subject below with CS2 and CS1 above in that order, subject on top with CS2 and CS1 below in that order, subject in the middle with CS1 above and CS2 below and so on.

Like all Bach fugues, the more you listen to it, the more you hear. Take for example the sudden rich harmony of the last two measures leading to the final cadence. Joseph Kerman, in his fine book on Bach fugues, The Art of Fugue, hears a bit of extravagant self-parody here (p. 14). Do you agree?

Here is Víkingur Ólafsson:

Wednesday, February 3, 2021

Bach: WTC, Prelude and Fugue in C major

|

| Click to enlarge |

And here is the complete score in the Neue Bach Ausgabe: